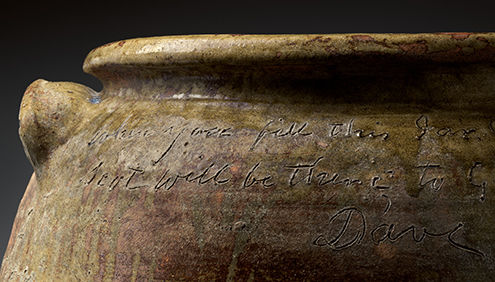

Hear Me Now, an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, opened this month. A wonderful video allows us to hear the thoughts and reflections of the curators. More importantly, through the art they have curated we are able to hear the voices of the makers, enslaved potters of great skill, put to work at Edgefield in South Carolina. As slaveholders and their enablers tightened laws aimed at restricting literacy, these makers spoke eloquently in local clay, the same kaolin (porcelain clay) that they and their families had worked, or still worked, in West Africa. More than this, they wrote on the pots they threw. Dave, a potter of immense talent, also wrote poetry.

In highlighting the reliance on highly skilled slaves in artisan production, the exhibition reminds us that the antebellum South was far from unique. Slavery has been ubiquitous in human history and we have no way of knowing, in almost every case, whether a work of pre-modern art was produced by an enslaved person.

It was certainly the case in the Roman world that skilled slaves made almost everything, frequently alongside those who had been freed and those who were born free.[i] Private slaves and freedmen were also employed in countless artisanal contexts.[ii]

Enslaved artisans led hard lives, but typically did so in far better conditions than those endured by industrial and agricultural slaves. I highlight here metal communities, since they extracted and smelted the ores to produce metals worked in countless smithies and workshops by artisans. Miners and smelters were frequently imperial slaves, perhaps criminals or prisoners-of-war condemned to their profession, but also those who happened simply to born to miners, and therefore were bound to the mines. A section of the Theodosian Code (CTh.), a compilation of laws produced in the 430s, entitled De metallis et metallariis, addresses the regulation of mines and miners, metals and metal-workers, and stone quarries. A law of 424 (CTh. 10.19.15) ruled that “if any person should be born from a miner and from any other stock, he shall necessarily follow the ignoble birth status of a miner”. Moreover, if miners should “seek to migrate to foreign parts, they shall be recalled to the family stock and the household of their birth status”. There was by then an established body of law relating to the flight of indentured miners, starting with a ruling of 30 April 369, which instructed provincial judges to provide support in identifying and apprehending vagrants (CTh. 10.9.5).[iii]

[i] The vast bibliography can be entered via N. Lenski, ‘Violence and the Roman slave’, in The topography of violence in the Greco-Roman world, eds. W. Riess and G. Fagan (Ann Arbor, 2016), 275-98.

[ii] A related law, issued just a month or two later, suggests miners had absconded to Sardinia by ship, and that ships’ captains were liable for a fine of five solidi for each miner they helped to escaped. Evidently, the practice continued, and a further law of 378 returned to the matter of miners absconding to Sardinia, notably gold miners. There were certainly fewer slaves working the mines than in earlier centuries.

[iii] C. Hawkins, Roman artisans and the urban economy (Cambridge, 2016), passim, especially 84-5, 87, 89, 91-2, 97, 126-8, 130-91.